By Joseph Sherlock, Rachael Grainger, Shaye-Ann McDonald and Michael Daly

Americans’ trust in government is at one of the lowest points in history.

While the origins of this distrust are complex, some of this originates from a lack of clarity on the intricacies of government operations, how the public benefits from government efforts, and the work being done by government employees.

Trust in Elections Has Continued to Deteriorate

The growing spread of misinformation and political and affective polarization has led many Americans to distrust both the government, each other, and out-group members. For example, election confidence rates have continued to erode, decreasing from 82 percent to 84 percent to 77 percent for the 2012, 2016, and 2020 elections, respectively. Confidence has also continued to be skewed towards those affiliated with the winning party, meaning voters have been more confident in the results when they are in their favor.

Despite consensus among independent academic and journalistic investigations that voter fraud is rare and extremely unlikely to determine a national election, tens of millions of people believe the opposite. Polling conducted in September 2020 suggests that nearly half of Republicans agree that election fraud is a major concern associated with expanded mail-in voting during the pandemic. This study similarly found, after analyzing over 55,000 media stories, that both Fox News content and Donald Trump’s campaign were far more influential in spreading inaccurate beliefs than Russian trolls or Facebook clickbait.

Transparency as a Potential Solution

However, there is evidence that it may be possible to increase the trust, satisfaction, and goodwill felt toward the government by increasing the operational transparency of the effort involved in delivering public services. Creating this sense of transparency has notoriously been a weak point for many government organizations. Furthermore, people do not clearly understand how it works behind the scenes for the relatively novel, more recently popularized mail-in voting process.

In The Submerged State, Mettler argues that increasing operational transparency, or transparency regarding the hidden work that the government performs, can improve government perception and increase trust. She explains that submerged policies — those that fail to provide evident benefits — are often misunderstood. This lack of understanding may have adverse effects on individual evaluations of their government.

Another recent study found that individuals exposed to an operational transparency treatment had significantly higher government trust levels. Buell found evidence that revealing operational transparency increases trust even in settings like government services, where this can be lower. An app distributed by the City of Boston allowed residents to submit service requests to their city government using their mobile phones. Users who viewed photos of city workers responding to their service requests were more likely to continue using the app over the next 13 months. This demonstrated that by providing some degree of operational transparency, governments can foster sustained civic engagement.

Interventions may leverage transparency not just by providing information on the process, but also by informing citizens about the effort and people underpinning their government’s services. Drawing upon these insights, we designed a study to investigate how public trust in elections was impacted by transparency-based content, and if the effectiveness of this strategy varies based on the framing of the transparency prompt.

Testing How Operational Transparency Impacts Trust

With widespread misinformation around mail-voting results for the US 2020 election, we hypothesized that exposing operational transparency of the mail-voting process would reveal higher trust in the government. We were particularly interested in the impact of election transparency on people’s trust in different levels of government (local, state, and federal). We explored multiple transparency prompts focused on detailing the mail-voting process in the United States.

We ran an online randomized control trial (RCT) with 942 MTurk participants in eight states. Participants were randomized into one of two control groups (random video or infographic) or one of four treatment conditions. They were either shown 1) a CNN video about how the process of mail-voting works across the United States, 2) a video with an overview of how the ballot tracking process works, 3) a video of the mail-voting process for specific counties in their locality, or 4) showed participants an infographic that outlined the “Life of an Absentee Ballot” and what a voter needs to do for their ballot to be counted.

Some Key Findings

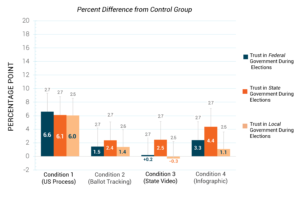

Our first transparency condition (US mail-voting transparency) produced significantly higher trust than all other conditions and the control group. The 6 percentage point increase was consistent across federal, state, and local government trust levels. The other conditions produced modest increases in trust. Contrastingly, our state-specific processes intervention decreased trust in local government during elections.

Figure 1: Graph showing changes in government trust with the 4 transparency interventions

Interestingly, we also found that the US mail-voting transparency condition produced significantly (around 12 percentage points) higher trust in the federal government for people who voted for Trump in 2020. This was despite the video being from CNN, a news source that tends to share left-leaning content. Meanwhile, both the US process and infographic transparency conditions produced a significantly higher understanding of mail-in voting processes compared to the relevant control groups.

What Does This Mean for Election Administration?

These initial findings prove to be promising, as they indicate that operational transparency is a tool that can be leveraged to increase trust in elections and varying levels of government. These results however may not apply broadly. As noted, trust was either negatively or slightly impacted for participants shown state-specific content, hinting that there may be drawbacks to revealing highly specific operational transparency, especially concerning government.

State-specific videos focused on individual counties could have produced the effect Buell refers to, where he suggests that credibility decreases when people see that those best efforts led to poor results. This reinforces the perception of the inadequacy of an organization. Similarly, there have been countless claims of election fraud and calls for election audits across the US. These state-specific claims can easily result in a single state-based transparency intervention being less salient than the continuous contradictory information on that state.

Regardless, these findings imply that higher-level transparency or a more general approach to sharing the mail-voting and other election-related processes could be useful. As we near the 2022 midterms, disseminating content around general US election systems seems to be a simple, easily applied, and scalable solution that could help the election administration to build trust levels in the election process.

This study was done in collaboration with The Brennan Center for Justice.

This article was edited by Shaye-Ann McDonald.