By Shaye Hopkins, Kate Fox, Toni Castro Cosio, and Hans Frech La Rosa

As humans, we all want to live good and fulfilling lives. This often means living a happy life and doing things we care about. Furthermore, we share a desire to become exceptional in doing the things we care about. That is, we wish to develop expertise in subjects or activities that align with our interests. But what makes humans of the same capabilities differ in developing expertise, and how can we harness those attributes for our own achievement?

Despite the persistent popular belief, experts aren’t born that way. Across domains, notably consistent traits include more intuitive knowledge and pattern recognition. Otherwise, grit and endurance play a part in their evolution, as do rigor and repetition. Still, from Picasso to Michael Jordan, there are several gaps in understanding how key facets play a role in becoming an expert.

How People Develop Skills

Our lived encounters show us that expertise is achievable, but we also know that it is difficult. Behavioral economics research highlights the continuous conflict between what we innately desire and the activities correlated with getting there.

The development of expertise begins, of course, with the development of skills. To date, research has attempted to solve common barriers to skill development, emphasizing the need for both deliberate practice and the motivation to do it consistently.

1. Deliberate Practice

Much of Ericsson’s extensive work on expertise highlights that it is more generally accessible than we might initially think. This means that skill development across domains isn’t only contingent on predispositions (e.g., height or perfect pitch). Though these factors do play a role, there is another key piece — deliberate practice. As a result, his research centers on the adaptability of the human brain and how maximizing this adaptability is key to building expertise.

2. Motivation

Otherwise, research has focused on hedonia (pleasure-based motives) and eudaimonia (or motives to achieve your best self) and the relevance of the two for well-being and efficacy. Ryan and Deci, for example, note that there is evidence that some individuals are intrinsically motivated by finding less instantly gratifying tasks interesting or enjoyable. This allows them to engage in such activities consistently and well. They note that even though this intrinsic motivation is usually linked to a specific activity of interest, understanding it is an important aspect of growth in skills and knowledge. Meanwhile, Milkman et al. note that when making choices, we often discount the future benefits of those activities for more immediate satisfaction, referred to as the “want-should” conflict. The result is that behavioral interventions often focus on altering the choice architecture to increase extrinsic motivation through methods like temptation bundling, or bundling instantly gratifying and less immediate rewards, to help fight against the difficulty of doing these tasks.

Together, there is strong evidence that these factors (practice, motivation, and choice architecture) play vital roles in goal achievement and skill development; meaning that it is necessary to have motivation and systems in place that allow you to push through to continue practicing deliberately to the point of expertise. Building on these findings, research shows that, when driven by the aforementioned intrinsic motivation and learning experiences, individuals can build upon their skills and reach peak performance, or expertise. They further highlight that peak performance is linked to experiencing positive emotions such as joy.

The Missing Piece: Joy

Joy & It’s Relevance to Expertise

Taking existing research together, there is a missing piece to consider — joy as a driver to developing expertise. While significant research delves into contributors to long-term achievement in one’s field, other studies shed light on the experience of joy and its importance. However, little evidence exists on the apparent overlap between expertise and joy.

Joy, though less studied than other related emotions like happiness, is a vital part of the human experience due to its connections to general well-being and flourishing. We often experience joy as a positive state that emerges from positive experiences, like achieving a goal or other favorable experiences. Intuitively, joy’s characterization implicitly positions it as the connective tissue that joins intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Finding joy in deliberate practice is what can get people to push through to the point of becoming an expert.

Joyful Expertise

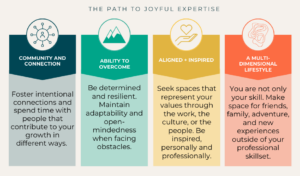

In our pursuit of expertise, we often overlook the importance of “finding joy” in the journey. We’ve explored why certain individuals overcome what others perceive to be unbearable rigor, and how the experience of joy helps determine their path to expertise. In doing so, we’ve come to define this phenomenon as “joyful expertise”. To cultivate joyful expertise, we must integrate strategies that enhance skill development and enrich our lives with fulfillment and happiness. Based on this, we hypothesize that useful guidance toward achievement lies both in the “how” and “why”. We explore connection, resilience, inspiration, and balance as key factors for joyful expertise, each helping to drive humans toward their goals. Our framework for achieving joyful expertise is as follows:

Existing research and intuition indicate that some key elements of experiencing joyful expertise require a few notable ingredients. These include the following:

- Connect and Cultivate Community: As humans, we thrive on connection. There is evidence that interpersonal connection, having mentors, and being a mentor, positively impact well-being and happiness while also facilitating skill development. Learning from those who are experts and being able to teach others further inspires us. This similarly aligns with Ryan and Deci’s findings on the importance of connectedness for motivation. They note that activity motivation stems from the result of feeling valued by significant others to whom they feel (or would like to feel) connected, providing a sense of belongingness and connectedness.

- Embrace Grit and Resilience: Notably, one of the inevitables on the road to mastery (or non-mastery) is difficulties. Determination, resilience, and grit are key to getting to the peak. Achievement is not about avoiding difficulty, but about bouncing back stronger. Finding ways to push through these obstacles and learning from difficulties is ultimately what allows us to continue to perform successfully.

- Find Aligned Environments: Find environments in which we thrive. Surroundings shape our journey toward expertise and misalignment can easily steal our joy. It’s essential to seek out environments that resonate with our values, passions, and aspirations. When our environment aligns with our goals, we thrive and are easily able to work toward building our skills. Conversely, misalignment drains our energy and dampens our spirits. By surrounding ourselves with supportive spaces that nurture our growth, we invite joy into our pursuit of expertise.

- Embrace Holistic Well-Being: Another piece lies in ensuring more general well-being outside your skill. Research and our own experiences show that it is also necessary to maintain balance through nurturing relationships with family and friends, new experiences, and making space for activities outside of your primary skill set. Engaging in diverse experiences and cultivating holistic well-being not only enhances creativity and resilience but also fosters a sense of fulfillment and joy in our more general goal of living rich and meaningful lives.

Some Implications

Whether the goal is to become an expert in an area or just generally build a skill, there seem to be factors that play a vital role. These seem to be some of the building blocks to building not only expertise but joyful expertise — an experience characterized by joy during the activity and more general flourishing in the area. Key ingredients include good communities that enable skill development, building resilience, and finding environments aligned with interests and values. It is also vital to ensure balance in life. This means resting, exploring, and pursuing a range of activities that not only contribute to expertise, but also contribute to joy.

This article was edited by Shaye-Ann Hopkins.