By Julian Christensen and Donald P. Moynihan

Politicians may not agree on much, but they do seem to agree on the value of data and evidence for policymaking. Government after government have constructed systems designed to collect and distribute data in a bid to figure out what works. The goal of such systems is to make government more informed, more evidence-based and more rational. But someone still needs to use that information before it can affect the policies being made. Our research shows that not only are politicians subject to the same sort of psychological biases that lead them to misinterpret policy information as everyone else, they are more resistant to efforts to reduce those biases, and more likely to double down on their political beliefs even when at odds with the evidence at hand.

The UK offers one example of the evidence-based movement in government. In the beginning of this century, the Secretary of State for Education and Employment, David Blunkett, called for “social scientists to help to determine what works and why, and what types of policy initiatives are likely to be most effective.” Such calls are not new. Since the 1960s, governments pushed the adoption of randomized-controlled trials to understand if social programs work, and performance measurement requirements to track outcomes of schools and other important public functions. Over time such efforts have become more systematic, typified by the US Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018, which creates learning agendas for individual government agencies.

The appeal of evidence-based policymaking is clear: it promises a systematic way to increase the attainment of political goals. However, we cannot understand the role of evidence in policymaking without understanding how policymakers interpret information. The potential for evidence to become evidence-based policy depends upon how policymakers use that information. Our prior research shows that people, including politicians, often interpret information to reach conclusions consistent with their political identities and attitudes, for example by playing down the importance of information if it does not support the conclusions they are politically motivated to reach. Such motivated reasoning makes it less likely that evidence will be judged on its merits.

Motivated Reasoning Distorts Decision-Makers’ Evaluations of Policy Information

If politicians make biased evaluations of policy information, it is likely that their use of the information will be biased as well. To test the effects of motivated reasoning on the use of policy information we ran a series of experiments with elected politicians (Danish city councilors) as well as representative samples of the Danish public. In Denmark, city councilors are responsible for the delivery of core public services, such as education, childcare, elder care, and employment activities, and their policy portfolio accounts for about half of all public expenditures in Denmark.

In one experiment, we asked respondents to choose which provider of elder care services performed best, based on a table of user satisfaction data. In every case, there was a correct and incorrect answer, but some simple calculation was required. For some subjects, the providers were labeled with the neutral names ‘provider A’ and ‘provider B’ meaning that the information was completely depoliticized. For others, information was presented in ways likely to trigger politically motivated reasoning: one provider was labeled as municipal (public), while the other was private. In Denmark, contracting out elder care and other public services has been at the center of party conflict for more than two decades. Local politicians are at the frontline of this debate, as they must regularly decide on whether or not to contract out specific services.

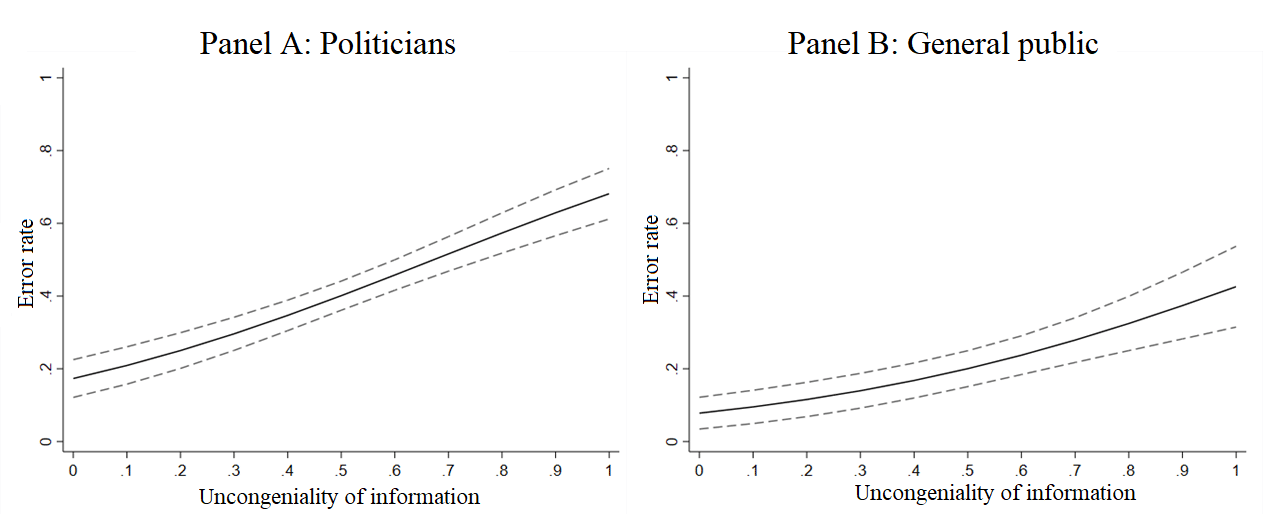

The design of the experiment allows us to understand how accurately politicians process simple policy information under conditions when the information is either depoliticized or likely to trigger motivated reasoning. When the numbers are depoliticized, respondents do well at identifying the best performing provider. However, in conditions that trigger motivated reasoning, politicians’ ability to accurately interpret information depends upon whether the information is congenial to their political beliefs. For example, a politician on the left who opposes private delivery of public services is less likely to accept data that shows a private provider doing better. The figure below maps out these patterns of error, which hold among members of the public and politicians alike. The less congenial the policy information is, the higher the error rate. Politicians correctly identify the best-performing provider 92% of the time when the information fits with their political beliefs, but only 57% of the time when it does not.

Figure: The impact of information (un)congeniality on respondents’ ability to identify best performing provider

Justification Requirements Reduce Biases Among the General Public but Strengthen Biases Among Politicians

Is there anything that can be done to reduce the effect of ideological biases in how politicians use data? To help answer this question, we tested the effects of one debiasing intervention: asking people to justify their evaluations. Justification requirements are an old technique, which forces people to slow down and look more carefully at the data in the knowledge that they must be able to explain their decision processes.

We ran a version of the above-described experiment, with one big difference: We asked subjects to write an argument for their answer. We expected this to reduce the impact of attitudes on people’s evaluations but while such debiasing effects were found among members of the general public, the reverse was the case among politicians. When required to justify their evaluations, politicians doubled down and relied more on attitudes and less on policy information. In other words, it is easier to change the mind of the public using policy evidence than it is to change the views of the politicians that represent them. Our findings therefore pose an obvious challenge to the idea of evidence-based policymaking.

An intriguing question is why these differences exist between politicians and their voters? Is it selection – people with stronger ideological beliefs become politicians? Or is it the job environment – politicians become accustomed to sticking to their guns even if contradicted by the evidence at hand? Although our experiment was not designed to test these questions, we can offer some suggestive evidence that points to the latter explanation.

If the selection explanation drove our findings, we would expect members of the public with a strong interest in politics to act more like politicians, that is, be more resistant to our debiasing intervention than others who are less politically engaged. This is not the case. In fact, the debiasing effect of justification requirements among voters is driven by these very politically interested individuals, meaning that they behave less instead of more like politicians.

If the job environment effect is driving the results, we would expect that more experienced politicians would be more resistant than their newer counterparts. Danish city councilors are elected through municipal elections every four years. Around 40% of our respondents had, at the time of the data collection, been elected for 1 year whereas the rest had been elected for 5 years or more. We find the bias-strengthening effects among politicians to be driven by experienced politicians: Justification requirements have no effects among recently elected politicians but strong bias-strengthening effects among their experienced colleagues.

As noted, these last analyses are explorative and other designs are needed to make us more certain about the causal effect of being a politician. However, the findings suggest that the bias-strengthening effects of justification requirements among politicians reflect a process where elected officials learn to think and behave ‘like a politician.’ Politicians are constantly demanded to justify their views by constituents, the press or other politicians, but risk being labeled a “flip-flopper” if they don’t maintain ideological consistency. So they become more willing and able to use information to defend their political views rather than to challenge those views. As a result, a justification requirement that causes a member of the public to pause and revisit their argument is an invitation for a politician to double down. The grand irony is that politicians have built structures of evidence-based policymaking that are at odds with their own behavioral approach to policymaking.

This article is based on the article “Motivated reasoning and policy information: politicians are more resistant to debiasing interventions than the general public” to which there is open access through Behavioural Public Policy (doi:10.1017/bpp.2020.50).