By Amy Bucher

Theoretically, “digital health,” or interventions that rely on technologies such as websites, mobile phones, connected devices, and the like to help people improve their health, should be convenient, relatively low cost, private, and make it easy for individuals to find the right tools for their needs from a range of options. After all, technology scales and digital devices seem ubiquitous. But that hasn’t quite panned out.

One reason is that there are systemic discrepancies in who uses digital health tools and who doesn’t. For example, research has found that Black and Hispanic people, particularly older ones, are less likely than white people to use technology for health-related purposes. They are also less likely to own a computer or to use digital health interventions. Additionally, people who live in rural areas may not have sufficient broadband access to use high-bandwidth tools. When people in these groups aren’t explicitly considered in design, there’s a chance the resulting intervention may not work for their needs.

Then there is the matter of the barriers that stop people from doing the actual health behaviors. More than 20 years into the era of modern digital health, we haven’t solved most of healthcare’s most wicked challenges. People are still non-adherent to their medications, behind on recommended preventive care and screenings, and out of alignment with expert recommendations on lifestyle behaviors such as exercise and sleep (none of which was helped by the COVID-19 pandemic). It may be that the right tools to solve these problems don’t exist, but the evidence suggests the problem is more about having the right set of tools for all people and a good way to matchmake the individual to the intervention.

Tackling COVID-19 Vaccination

At Lirio, we found ourselves tasked with building a behavioral intervention focused on driving COVID-19 vaccination, right as vaccines were first coming available in the United States. Aside from the supply limitations at that time, there were also a range of reasons why some people did not want to get vaccinated right away. Early COVID-19 research revealed a broad and evolving set of barriers complicating people’s willingness to receive a vaccination, from access issues to health concerns to educational needs to belief in conspiracy theories. We knew we needed to design an intervention that could speak to as many of those barriers as possible, while also being appropriate for a population that was demographically and socially diverse – the entire patient population of a large health system in a southern US state.

Demographically, this population included many people from the groups that don’t use digital health tools as much, including Black and Hispanic people and people living in rural communities. These are the same groups disproportionately affected by health conditions that could be avoided or modified through behavior change. Take COVID-19; a systematic review of health data through the first year of the pandemic found Black and Hispanic people experienced higher rates of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths than white people. We therefore wanted to leverage tools for our intervention that are well-used by these groups, such as email and text messages, which also happened to be modalities our client health system used with their patients. While we knew that no single intervention could possibly address every barrier, we wanted to address as many as we possibly could, and especially those likely to be most common in our target patient population.

What’s a behavioral designer to do?

Combining Toolkits from Different Design Disciplines

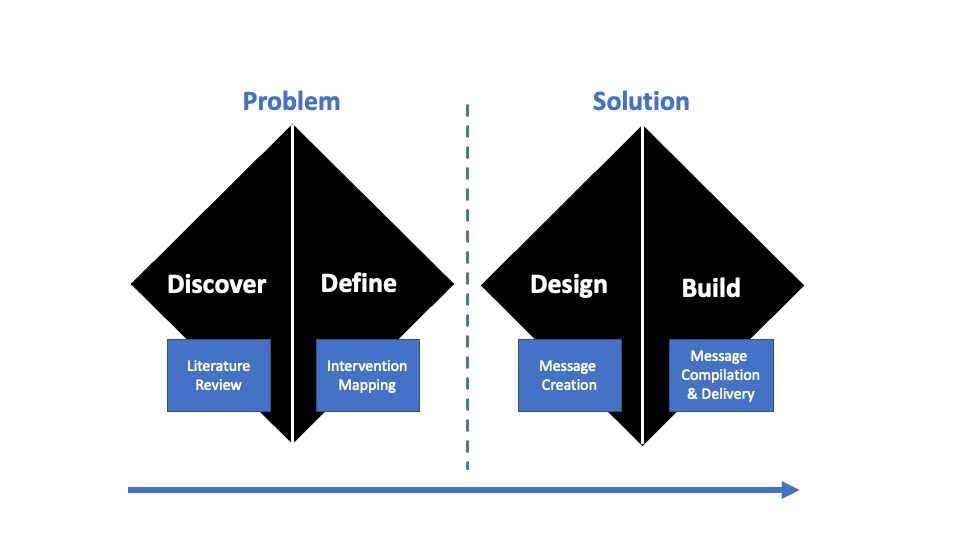

We decided to deliberately layer our existing behavioral design process with a tool from the human centered design school of practice. The Double Diamond model was created by the UK Design Council in order to visually communicate a universal design process. The Double Diamond alternates divergent phases, in which designers gather and generate new information and ideas, with convergent phases, where designers focus their process on a limited number of strategically focused opportunities. A great metaphor to understand the transition from divergent to convergent phases comes from Marie Kondo’s KonMari method of organization, in which people lay out all of their items in a category such as books to inventory their belongings (divergent) and then select only the ones that “spark joy” to keep (convergent). Similarly, designers may go through a brainstorming phase in which they encourage expansive idea generation (divergent) but then review the resulting list of ideas through a strategic lens to prioritize only the most promising (convergent).

One of the most useful aspects of the Double Diamond is how it explicitly sets expectations around when a phase is divergent or convergent. When we think of doing the formative research that will lead to an intervention design, and know we must serve a diverse group of people with that intervention, a divergent mindset is needed. Divergent thinking can be challenging when it comes to intervention design (especially in the face of an urgent public health crisis!), but it forces us to systematically evaluate a broader evidence base.

In combining our behavioral design process with the Double Diamond, we found we were able to layer our existing steps along alternating divergent and convergent phases. The phases and activities end up being (Figure 1):

- Discover phase includes the literature review and any primary research that we do to understand the determinants of the target behavior in the population who will use the intervention. In the case of our COVID-19 program, administered to a diverse population of health plan consumers, that meant casting a broad net on determinants of COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. (Given the timing of our intervention development, prior to widespread vaccine rollout, it also meant surveying immunization barriers more generally.)

- Define phase is where the team evaluates which determinants can be adequately addressed with our intervention toolkit and decides on the solution components. Knowing that we would rely on email and text message to deliver the intervention, we excluded vaccination determinants such as “lack of environmental resources” which are not directly mutable via messaging. This convergent phase leads to a discrete number of behavior change techniques, such as action planning, emotional consequences, or information about others’ approval, deployed within the intervention.

- In the design phase, we develop the message content and visuals for each of the included intervention tactics, as well as eligibility criteria for participation in the intervention and supporting materials such as consent forms and opt-in language. This divergent phase is an opportunity to creatively operationalize the behavior change techniques included in the intervention.

- Finally in the build phase we enable our intervention on the technology platform and ready it to deploy. In our case, we use a behavioral reinforcement learning algorithm, which is a type of artificial intelligence that learns from people’s behavioral responses what types of messages are the best match to get them to take action. The platform compiles complete messages from components (think subject lines, body copy paragraphs, and images) that are part of a library based on what the recipient has responded to in the past. The message library is essentially narrowed for each individual to only suitable options.

Figure 1 – Behavioral Double Diamond.

This combined method of design, along with the particular reinforcement learning technology we used, allows us to pattern-match between the behavior change techniques we selected to cover the broadest possible set of behavioral determinants and each individual; ideally, people feel that the messages they receive are relevant and appropriate for their specific needs.

The Behavioral Double Diamond

A major benefit of adapting the Double Diamond for use in behavioral design of health interventions is codifying a divergent research phase in the development process. Health inequities are a persistent and thorny problem that cannot be solved if we keep designing just for the most privileged or prominent groups. We see the Behavioral Double Diamond as a key tool in equitable intervention design.

Leveraging tools familiar to other types of designers also smooths collaborations between our functions. Behavioral designers rarely work in isolation; being able to share a common language and mental model with our UX counterparts improves our process and our output, and also makes it easier to share our particular vocabulary and tools.

Finally, we believe this process equips us to respond more quickly to public health crises like COVID-19 with the development of suitable interventions. In a situation where time is of the essence, the target behaviors are not yet well-understood, and the intervention population is diverse in their behavioral determinants, the Behavioral Double Diamond will help us serve more people, more quickly and more equitably.

Behavioral double diamond image is from Ford, K. L., West, A. B., Bucher, A., & Osborn, C. Y. (2022). Personalized Digital Health Communications to Increase COVID-19 Vaccination in Underserved Populations: A Double Diamond Approach to Behavioral Design [Perspective]. Frontiers in Digital Health, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.831093

Vaccination illustration (featured image) is a sample from Lirio’s COVID-19 vaccination intervention and was designed by Karilyn Housworth.

This article was edited by Mariliis Öeren.