By Dominik Jung

Investing in the stock market is a complicated and risky undertaking for private households. Investors face numerous decisions: Should I invest in stocks or bonds? Should I buy passively or actively managed investment products, or should I try something new like Bitcoin? Furthermore, private investors often lack in financial knowledge and experience to make optimal decisions. As human beings, they are also subject to limits in cognitive capabilities, motivation, and willpower.

Dual System Theory

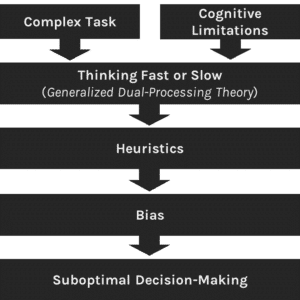

However, from psychology we know that we have a clever mechanism for managing our limited cognitive resources. Nobel Prize Laureate Daniel Kahneman distinguishes two cognitive systems that help us to manage our environment “economically”.

- A “System 1”, which he associates with fast, spontaneous, emotional and intuitive thought processes. Its processes run parallel and often in competition with the consciousness processes of a slow “System 2”, to which Kahneman assigns effortful thinking.

- This System 2 is busy with judging things logically, assessing them against rational standards, etc. – everything we tend to refer to as “rational” thinking

In order to make fast and cognitively effortless decisions, the intuitive System 1 uses simple heuristics (rules of thumb) which usually lead to correct decisions and appropriate behavior in everyday life. In some situations, however, its competence does not seem to be sufficient. According to Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, this leads to suboptimal or wrong decisions.

Figure 1: Why we make suboptimal financial decisions

Decision Support Systems

In order to overcome the shortcomings of human decision-making, information systems researchers aim to design and develop financial decision support systems. These information systems help users to handle the complexity of financial decision-making and make more rational or deliberative decisions. Robo-advisors are such decision support systems that aim to provide independent advice, and support private households in investment decisions and wealth management. However, there remains a need to investigate the systems’ design and usage and thus their ability to support financial decision-making.

Decision Inertia in Financial Choice

Addressing this research need, I implemented a simple prototype of a robo-advisor and measured decision-making in a series of choices. Furthermore, I focused on the capability of robo-advisors to overcome a specific bias in financial decision-making – decision inertia. This is the tendency of humans to stay with a previously made choice, independently of the initial decision’s outcome. In the domain of finance, people may stick with an investment regardless of the gains or losses it has made. Decision inertia also shows in other economic areas: For instance, some customers of the German telecommunications provider Telekom retain contracts for analogue monthly-paid telephones from the 1980s, despite the fact that the technology shift to voice over IP (VoIP) has rendered these telephones utterly useless. Similarly, about 2 million US-American customers of AOL still paid monthly fees for dial-up internet connections in 2015.

Nudging Robo-Advisory Users

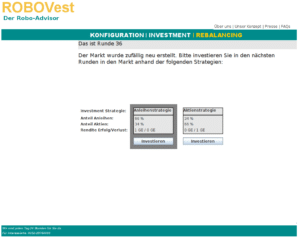

To help users of my robo-advisors, I implemented different nudges to decrease users’ tendency to show decision inertia (see the other popular inertia studies of Pitz et al., or Alós-Ferrer and Achtziger). Following established decision inertia research, my study relied on a dual-choice belief-updating task (so called “Dual-Choice Paradigm” – see examples here and here) to measure decision inertia. In my task, the participants were asked to virtually invest money with the robo-advisor in a market simulation, with rewards given for successful outcomes. More specifically, participants were confronted with an initial investment decision and a subsequent rebalancing decision, which were repeated in multiple rounds. In each round, the participants had to decide between two different investment strategies (see Figure 3). Both strategies had different success rates, dependent on the market state that was unknown to the participant.

The task of the participants was to make a successful financial decision as often as possible, because the payoff of the experiment depended on the outcome of their investments in each round. The participants could do that by guessing the state of the market, based on the feedback of the first investment decision. Decision inertia showed in the participants’ tendency to stay with the same choice as in the first draw, independently of whether that decision resulted in a gain or a loss.

Figure 2: Robo-advisor welcome screen |

Figure 3: Robo-advisor investment screen |

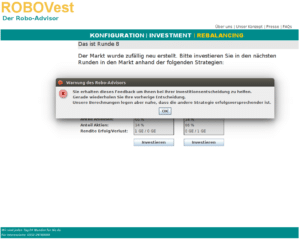

Figure 4: Default nudge robo-advisor screen |

Figure 5: Warning nudge robo-advisor screen |

To reduce decision inertia, I made use of two very successful choice architecture tools: defaults and warnings. Experimental participants were randomly assigned to receive either one of these two nudges or no nudge (the control condition). Defaults have been successfully applied in many other domains to nudge people in contexts of inertia or uncertainty. Decision-makers who are uncertain in their decision, or do not know how best to decide, perceive the default as a recommendation or socially desired option and are therefore more inclined to follow it. In my study, I implemented the default by highlighting the investment strategy (see Figure 4) and setting it active (participants could choose it by just pressing “Enter” or “Space”). Hence, defaults tackle decision inertia on a System 1 level.

The second nudge tested in the experiment, warning messages, relies on cognitive feedback and has been successfully used in financial decision support systems and other economic decision environments to reduce biased decision-making. The rationale behind this is that if participants are subject to inertia, warning messages building on cognitive feedback should encourage biased decision-maker to reconsider their decision and, if necessary, to consider alternative options. To activate System 2 resources, we confronted the participants when they showed decision inertia for the first time with the following message: “You are receiving this feedback to help you with your investment decision. As you are about to repeat your previous decision, please be aware that our calculations suggest that the other strategy is more promising.” (see Figure 5).

Results

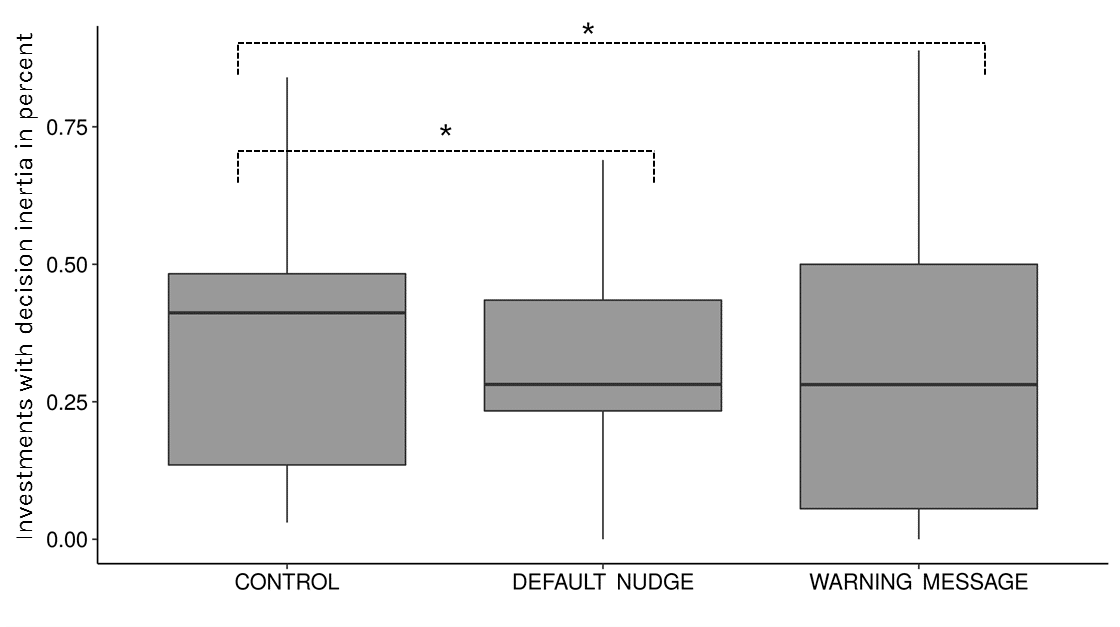

The results of the experiment showed mean rates of inertial investment decisions of 42.1% in the control condition, 29.8% in the default nudge treatment, and 27.4% in the warning message treatment. Statistical tests showed that nudged groups had significantly less decision inertia than the control group, even when other factors, such as financial literacy, risk aversion, or age, were taken into account.

Figure 6: The control group (without nudges) compared to the nudged groups

Here we see clearly, that in both nudge groups the rate of decision inertia is much smaller than in the control group, suggesting that nudges can help to reduce inertia in financial decision-making. However, if we take a look at the data distributions, the boxplots illustrate that the two nudges worked quite differently. In particular, the default nudge resulted in a skewed distribution toward greater decision inertia. This may be evidence of ‘reactance’, a psychological state that occurs in response to a threat or restriction of freedom. The motivational component of reactance involves individuals striving to restore threatened freedom. We know this effect in marketing, for example, when the supply of a product is artificially restricted and the freedom to choose certain products is threatened. As a result, reactance is triggered and the goods appear even more desirable than before. What makes reactance particularly relevant is the finding that it can also occur as a response to perceived influence and manipulation. In this experiment’s default condition, some participants may have deliberately chosen the biased option as a consequence of a reactance, reducing the effectiveness of the nudge.

Implications

Considering an ever-increasing number of decisions made in digital environments or at least supported by digital technology, the findings of this study have important practical implications. In the domain of investment decisions, results show how robo-advisors can help investors overcome decision biases. Furthermore, we see that system designers should be careful with the use of defaults to nudge customers of a robo-advisor towards better investment decisions. Even if the effect of defaults is stronger, they should be aware that reactance may reduce their effectiveness. Another aspect speaking against the use of defaults on their own is evident in robo-advisors’ role to guide their users, which includes the provision of tutorials, knowledge databases and so on. Warning messages are more consistent with this mission. They activate System 2 processes and can make the user more sensitive to biased financial decisions in the future – even if their effect may be lower. Robo-advisory designers could potentially eliminate reactance from nudges by combining different nudges, such as defaults and warnings, where the warning message provides a justification or disclosure of the default. A combination of these or other nudges seems to be a promising pathway and underlines the need for further research.

Note: The text is revised and adopted from Dominik’s PhD thesis “Robo-Advisory and Decision Inertia- Experimental Studies of Human Behaviour in Economic Decision-Making” (2019). The presented experimental study has been published as: Jung D, Weinhardt C (2018): Robo-Advisors and Financial Decision Inertia: How Choice Architecture Helps to Reduce Inertia in Financial Planning Tools. In: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference of Information Systems (ICIS 2018). San Fransisco.